Two Backpacks

Chapter 18 - Hue Citadel and the DMZ

The roads between Hoi An and Hue are bumpy and washed away in some areas, slowing our progress north. Our route takes us passed China Beach, where American soldiers spent their time on R&R, away from the ferocious war in Vietnam, and also famous for the song lyrics written for the television series of the same name.

Now, China Beach developers are building a vast tourist resort with multi-nationals building grandiose hotels around the bay. Dha Nhang Bay itself is spectacular, even in the rain and mist.

Our hostel for our stay in Hue is in the city’s backpacker area, away from the citadel, Hue’s main attraction. But our room is comfortable, and it’s good to be with other travellers again.

We decide to take a walk around the neighbourhood. It’s dark when we step from our hotel onto the pavement.

‘I don’t think we should go too far tonight. Let’s find somewhere to eat and explore tomorrow,’ I suggest.

‘Sounds fine with me,’ agrees Ron, whose back is a little painful after our bumpy four-hour bus journey.

The small restaurant we’ve chosen is also popular with other travellers. We get chatting with two Australian women who are also backpacking through Southeast Asia.

The food is good, the company better. It doesn’t take long before we’re exchanging stories and laughing at our mishaps. But just as we finish our meals, I see a monstrously large black rat running along the top of the wall behind where we’re seated.

‘Did you see it?’ I whisper to Ron, not wanting to freak out the girls sitting closest to where the rat disappeared.

‘See what?’

‘The rat!’

‘Where?’

‘There!’ I reply, pointing to the top of the wall as the giant rodent reappears and scuttles back the way it came.

The girls, intrigued by what’s going on, look to where I’m pointing just in time to spot the rear end and tail of the rat disappearing into a hole in the brickwork of the building.

‘Was that a rat?’ squeals Jaq.

‘I think it was,’ replies Ron. ‘But it’s gone now. Do you fancy another beer?’ he asks, hoping to distract the women.

‘Thanks, but I’m not staying, not if rats are running around,’ states Suzy. ‘But thanks for the company tonight; it’s been fun.’

‘I don’t fancy sitting here either,’ I add as a black-whiskered snout reappears from the hole. ‘Come on, let’s pay our bill and walk around the block.’

Early nights are becoming a thing with us, but I don’t mind, especially when I’m with Ron!

**********

With only two days in Hue, we’re up early the following morning. We’d noticed what appeared to be a popular bar the night before, one that also advertised English breakfasts; we decided to try it.

Not disappointed and ready for a walk, we set off towards the Imperial City, a walled enclosure in Hue’s citadel. The imperial capital of Vietnam during the Nguyen dynasty, its walls encircle palaces, shrines, gardens and villas. For one hundred and forty years, it was the ceremonial centre of the monarch until, in 1945, the monarchy ended. Seriously damaged and neglected during the Indochina Wars through the 1980s, it was only when the site was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1993 that restoration began.

Ron and I spend the day wandering through the site, stopping at one of the many street seller’s carts set up against the citadel’s walls for a lunch of delicious chicken-filled rice paper rolls.

The next day we’re off on a trip to the DMZ (demilitarized zone), the ‘no-go’ area that divided North Vietnam from the South.

Our transport for the day is an ancient bus that rattles its way through towns, villages and rice fields, its engine screeching whenever the driver tries to accelerate over fifty miles per hour!

With no air-conditioning, the fifteen passengers, Ron and I wind down the windows and allow the breeze to cool us.

The trip takes us over the 17th parallel, the military demarcation area between communist North Vietnam and the democratic South, established in 1954 under the Geneva Conventions.

There’s nothing to see now as we pass over the Ben Hai River that separated North from South, apart from loudspeakers perched on top of tall gantries from which propaganda was broadcast daily by the North Vietnamese.

‘Five miles on either side of the river is the demarcation zone,’ our guide tells us. ‘The south side saw some terrible battles,’ he adds without going into any detail.

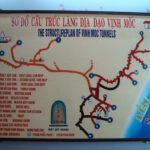

The trip continues eastward, towards the coast, to the Vinh Moc tunnels, a labyrinth of narrow, claustrophobic passageways home to hundreds of Vietnamese during the war.

Our guide leads the way to the entrance.

‘Please remember that what you’re about to experience is what life underground was like for men, women and children alike, people who lived underground for many years. You will see hollowed-out places in the tunnels, rooms for school, kitchen and work. This was a village like no other,’ he states as he sets off down the deep slope.

It’s impossible to chat as we follow, one after the other, with little room to stand, let alone converse. It’s easy to imagine living here, with small recesses dug into the tunnels to house families, while other spaces contain the remnants of kitchen equipment and tools.

Eventually, we climb upward, the rammed earth beneath our feet sloping towards the surface again. It’s a relief to breathe fresh air again when we exit from the tiny hole camouflaged by surrounding foliage.

We’re near the beach. I can hear the sound of breaking waves. I wonder how often the people who lived below ground could walk to the beach to wash in the seawater. Was it safe to do so? I look for our guide, keen to find out. But before I can ask, he’s ushering us back to our bus on a narrow track through the jungle.

Once we’re all settled again, the bus moves off.

‘He didn’t seem to want to answer many questions, did he?’ I say to Ron.

‘I know. It was so interesting. I’d liked to have spent more time there, looking around and visiting the museum.’

The final leg of our day trip is inland once more to view the Ho Chi Minh trail. The bus trundles along bumpy, potholed roads, climbing slowly upward through sparsely vegetated hills.

‘You will notice that nothing grows here,’ our guide tells us.

I see lush green hillsides from the bus window but no trees.

‘This is because the Americans sprayed the area with Agent Orange, a powerful herbicide used to eliminate forest cover and crops,’ he explains.

My thoughts return to the horrific photos sent back by the journalists of that time, the injuries caused by exposure, cancer, miscarriages and deformities that continue from one generation to another of Vietnamese and Americans exposed to the chemical.

It’s been a harrowing day, one that I will remember for all the wrong reasons.