Two Backpacks

Chapter 9 - A finger, an army and an Emperor's tomb - Xi'an

The sights of Tibet – the Potala Palace, the pilgrims and, of course, the debating Sera monks are experiences that will remain with me for the rest of my life. That I shared them with Ron makes them even more special.

We’ve only been travelling for two months, but already Ron and I have a wonderful connection. Our companionship sees us laughing at the same things, watching each other’s backs and occasionally stopping the other from doing something stupid!

It’s Ron who comes to my rescue as we’re leaving Lhasa. Our guide, Peter, has dropped us off at the railway station and, with our passports stamped, a customs officer then begins to check our bags.

Knowing that we’d have to do some cooking along the way, I’ve packed a small paring knife and a slightly larger knife which I use for meat and fish. The knives, are wrapped in a kitchen towel, have been through various baggage checks without any problems, including the train journey from Beijing three days earlier.

Unfortunately, an eagle-eyed soldier manning the conveyor belt, spots the knives and immediately orders me to open my bag. After a second or two of rummaging through my sweaters and underwear, he proudly produces the larger knife and holds it aloft while glaring at me accusingly.

Determined to stand my ground, but with Peter no longer available to translate, I go off on one, telling the officer I’ve been travelling with the knives for two months without any problem. The only trouble is, he hasn’t a clue what I was saying. Annoyed at my defiance, I can tell he’s stressed by my behaviour. It’s then Ron steps in.

‘It’s only a bloody knife, Sandi! Why are you making all this fuss? You can buy another one when we get to Xi’an,’ he declares, obviously exasperated by my behaviour.

He’s right; of course, he is. I’ve overstepped the mark. But the small paring knife had been my dad’s, and I didn’t want to part with it, not without a fight. I gesture to the guard that he can keep the larger knife but ask, with hands in supplication, that he allow me to keep the smaller of the two.

With an angry growl and a dismissive wave of his hand, the guard turns and walks off, my large knife tightly gripped in his hand.

‘Quick! Grab your bag and let’s go before he changes his mind!’ instructs Ron.

Still fuming, I grab my bra and lacy knickers the guard has pulled from my bag, shove them back inside, fasten the zipper and heave the pack onto my shoulder. Ron is halfway down the platform, looking for our carriage by the time I set off after him.

With our bags safely stowed, we sit side by side on one of the two bottom bunks.

‘What the hell was all that about?’ Ron asks once we’re settled. ‘You could have been locked up for carrying an offensive weapon! Why didn’t you just let the guard keep it?’

I’d been wondering the same thing. ‘It was a stupid thing to do. I know it was, but I didn’t like giving up my knives, especially to that idiot!’

‘I’ve never seen you like that before. You were so bolshy!’

‘I know. I’m sorry. I’m just grateful you were there to stop me from getting into more hot water!’

Ron looks at me. The corners of his mouth begin to turn upward; there’s a twinkle in his eyes. The next moment we’re both laughing.

‘It must be the red hair that does it! I’m calm and level-headed most of the time but upset me, and you’d better watch out,’ I warn him.

Laughing, Ron climbed up onto his top bunk. ‘Bring it on!’ was all he says before the lights in the carriage are turned out for the night.

**********

We spent another two nights on the train from Lhasa to Xi’an. Even though the journey is twelve hours less, somehow it seems longer – could it be a reluctance on my part to leave Tibet?

We share our compartment – six bunks again – with a man, a woman and their delightful little daughter, who is fascinated by Ron and his now somewhat overgrown beard!

Once in Xi’an, we find a meter taxi for the short trip to Xingzimen Hostel, only to find they don’t have our booking. The receptionist denied all knowledge of our arrival and subsequently sends us to another hostel around the corner. We follow her instructions only to find ourselves entering the same hostel from a road running to the rear of the property!

Frustrated, I ask, in pidgin English, to be allowed to use their internet to prove we have a booking. A few minutes later, the manager arrives and immediately apologises for their error after scanning through the email I’ve produced.

The building is old and set against the city’s wall, close to the South Gate. Within the hostel are small courtyards, a bar and a restaurant with ‘quiet’ areas on each floor. It’s charming. Our room, when we finally get there, is welcoming and comfortable, just what we need after experiencing the altitude of Tibet.

We take a couple of days to recover and wander through the city, visiting the Bell and Drum towers. We explore the Muslim quarter, where narrow streets form a labyrinth with snack stalls and tiny shops selling souvenirs, clothes, trinkets and foodstuffs.

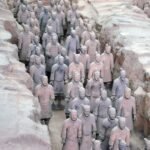

Feeling much more energised, we set off for the burial site of the first emperor of China, Qin Shi Huang Di and his Terracotta warriors. We’ve decided to forego a tour, instead, catching a bus outside the central rail station. The fare is only a few Yuan, and the journey is thirty minutes. The bus stops at the entrance to the site.

The first thing that strikes me is that the stalls that had stood in front of the entrance six years ago are gone, replaced by a full-blown retail park full of tourists eager for bargains, a sign of the times, I suppose.

I remember my friend Tom’s advice from my previous visit – to leave the main hall until last.

‘Come on, Ron, let’s see the chariots first,’ I suggest, reaching for Ron’s hand and leading him towards the entrance to Pit Two.

Inside, we pause for a few moments to allow our eyes to adjust to the subdued light. Ron remains quiet as he looks out at the chariots, warriors, and horses guarding their Emperor.

‘I didn’t imagine anything like this,’ Ron whispers. ‘It’s incredible!’

Before us are the remnants of chariots, horses and warriors, and thousands of bronze weapons. Although I’d visited before, I stood in awe once more of the magnificent spectacle before me.

Pit 3 is ‘U’ shaped and thought to be the command centre for the army. Here the soldiers stand facing each other, guarding their officers, while off to one side, a chariot stands behind four horses.

Finally, we walk into Pit 1, the largest of the three excavations.

‘Wait till you see this,’ I tell Ron as we walk into the hall. I watch as the enormity of what lies before him sinks in.

‘I thought the other two areas were amazing, but this is spectacular!’ Ron says as he looks out over the vast array of soldiers, some standing while others lay broken on the dusty, uneven floor.

We wander around the pit’s perimeter, occasionally stopping to take photos and marvel at the detail of the soldiers, an army built to protect the Emperor.

On our return to our hotel after our trip to see the Terracotta Army, we noticed a sign for the Banpo Museum, a Neolithic village located on the outskirts of Xi’an.

We’re up early the following day. We’ve nothing planned, so we decide to visit the Banpo museum.

The site is fascinating, with many artefacts, including axes, sickles, stone and pottery. The village built six thousand years ago is a typical Neolithic matriarchal community where women were the vital labour force while the men spent their time fishing.

‘Nothing’s changed then!’ I note as Ron and I read the board in front of the excavated village.

**********

Ron’s had enough of sightseeing. I’ve not.

‘Our you sure you don’t want to come with me to the tombs?’ I ask, knowing Ron’s already mentally settling down for the day with his computer.

‘You go if you want to, but I’ve had enough temples and tombs,’ Ron replies.

I go to the hostel’s reception and enquire about a tour of the tombs and Famen Si. I’m lucky; there’s still room on a trip leaving in ninety minutes.

‘Sure you’ll be okay on your own?’ I ask as I shove two bottles of water into my carry bag.

‘I’ll be fine. Enjoy yourself!’ Ron replies before returning his attention to his computer.

As I wait in reception for the tour bus to arrive, I think about Ron, our relationship and how far we’ve already come in our journey together. We’re both independent but also happy to share experiences along the way. If I’m honest, I like time to myself, time to explore, especially here in China.

The tour bus arrives on time. Our guide is a petite young woman with the darkest long black hair, a flawless pale complexion and a warm smile. Her English name is Mae; she tells us as she welcomes us to the tour. There are a few other laowais on the bus, but most passengers are Chinese.

We’re on our way to see the mausoleum of the Emperor Wu of Han (157–87 BCE). The site is in a tree-lined field with other lesser burial mounds in the distance. A little underwhelming, I’m glad when Mae asks us to board our bus again.

As the countryside flashes past our comfy, air-conditioned bus, I hope I’ve not made a mistake taking the tour.

A young Dutch couple is seated across the aisle from me.

‘How long are you in China?’ the young woman asks

‘Two months,’ I reply. ‘And you?’

‘We only have two weeks. It is not enough, I think,’ replies Heleen. Her partner, who she introduces as Kris, nods in agreement.

‘Where are you off to next?’ I ask, smiling at what I’ve discovered to be the routine questioning between backpackers.

‘Australia,’ Kris replies. ‘Have you been?’

‘I live there, in Perth. We’ve been travelling for two months,’ I state.

We travel in companionable silence for a while before Mae informs us that we are approaching Qi Ling, where Emperor Gaozong and his Empress, Wu Zetian, are buried, built in 684 AD.

Mae leads us down a gentle slope towards the entrance to Wu Zeian’s tomb. In the cool of the underground cavern, murals cover the walls, depicting the life of that time, the artwork intricate and detailed, the colours still vivid.

Above ground again, Mae leads the way.

‘We are now walking to Emperor Gaozong’s tomb,’ she states.

We do as instructed and follow on behind Mae, her umbrella held aloft, reminding me of an officer leading his soldiers into battle.

‘This is Spirit Way,’ Mae advises as we begin what is more a hike than a pleasant walk.

It is over a mile long. We pass stone-carved statues of warriors and horses standing guard on either side of the extensive walkway. Along the way, I notice rows of figures, all with their heads removed.

‘These are foreign ambassadors,’ Mae advises our group, sensing our questions before we’ve voiced them. ‘No one knows why they are here or appear as they do.’

Did they upset the Emperor? Whatever they did, it must have been serious for their heads to be removed! I ponder as I walk past the rows of decapitated officials.

The walk to Emperor Gaozong’s tomb is tiring, especially in the heat of the day. When we arrive, there’s a magnificent view across the landscape to distant heat-hazed hills. There’s also disappointment. We’re unable to enter the tomb.

Mae smiles. ‘We are now going to the Famen Si,’ she advises our gathered, hot, sticky and tired group.

‘Couldn’t we stop at a café for half an hour?’ suggests an American man, his size not conducive to long walks in the heat.

Mae feels the enthusiasm for the tour waning. ‘We can take a rest for ten minutes,’ she concedes. ‘But then we must leave.’

Grateful for the break, I find shade under one of the many trees that border the Spirit Way and collapse on the ground. Rummaging in my bag, I pull out a water bottle and take a glug of the now-warm liquid. Cursing myself for not packing a hat, I improvise by wrapping my scarf loosely around my head before it’s time to set off in the midday heat once more.

Pictures I’d seen of the Famen Si were of a thirteen-tier octagonal pagoda, under which, so the story goes, a sliver of the finger bone of Sakyamuni, the founder of Buddhism, was found. During rebuilding in 1987, workers discovered an underground palace containing over two thousand treasures and jewellery surrounding a Tang mandala.

Gazing from the bus window, I search the landscape for the pagoda. Instead, my eyes are drawn to an enormous golden Buddha, while in the hazy distance, I see a massive monument of two hands clasped in prayer.

As we draw nearer, the enormity of the site becomes apparent. Once we’ve alighted from the bus, we must catch one of the miniature ‘trains’ to take us the four miles to the temple and museum.

Entering via the Prajna Gate, we pass the two reflection pools before continuing our way towards the temple, the old standing pagoda still standing against the brash new clasped hands of Namaste Dagoba.

We faithfully follow Mae from our little train and enter the pagoda. Subdued lighting only highlights the magnificent gold, silver and bronze artefacts on display, the details and intricacies of design worthy of something produced by machines today rather than nearly two centuries ago.

One particular display intrigues me – a bronze gyroscope. How did the Chinese manage to build such an intricate, technical piece? Where did these peoples obtain their knowledge? I miss being able to share my discovery with Ron. Instead, I look around for Mae. She’s nowhere to be seen. I make a mental note to find out more once I’m back at the hostel.

‘Thought you’d done a runner!’ is my greeting when I finally arrive back and find Ron in the bar, a cold beer in his hand.

‘Just a long day,’ I exclaim before taking the bottle Ron offers me. ‘What do you fancy for supper? I’m starving!’

‘Let’s go back to that restaurant that does toffee potatoes,’ Ron suggests.

Tomorrow we’re off to Hong Kong. We’re flying from Xi’an to Shenzhen and hoping to take a bus over the border. It should be exciting if, perhaps, a challenging trip.